When an event as seismic as last week’s shake up at Pitchfork takes place within a space as self-involved and eager to feelings dump as the nebulously defined music twitter discourse sphere, it’s no surprise that a ton of histrionic tweets, personal essays, and premature obituaries by outsiders and contributors alike have already flooded the internet. A lot of this writing has been insightful and cathartic, and you should read about the site from people much smarter and closer to this issue than myself (and definitely not from randos speculating on when pitchfork “fell off”). I especially recommend this personal account from the now laid off longtime Pitchfork veteran Marc Hogan, and this essay from contributor Craig Jenkins (along with others from Mark Richardson, Ann Powers, Chris Richards, and more I’m probably forgetting)

I was obviously spurred into action by the layoffs and the now infamous “folding in” of Pitchfork into GQ, but this piece was something I could have written about any number of things over the last year or so. It could have been about the similar sale and gutting of Bandcamp, the many “pivots to video” – hell, even in the course of writing this, the LA Times laid off at least 115 full time staff including friends and writers I admired as role models. At this rate, by the time you’re reading this, another publication might be shuttering its digital doors or laying off critical staff [edit: since writing this sentence, business insider laid off one of the very best young music writers working, Kieran Press-Reynolds].

As these body blows pile up, it can start to feel like a funeral very quickly. Every time another story breaks, I am brought back to these same drain-circling thoughts that have been plaguing me for some time now: what happens next? What does the future of arts and culture journalism look like? Are we fucked?

Firstly, before I try to talk us off that collective ledge, I would like to acknowledge the fact that everyone (including myself) is probably being a little dramatic. I still hold faith that there’s a way forward, and I think the people holding funerals for the album review or culture journalism as a whole are being just a little hasty.

I don’t want to downplay the catastrophically dumb decisions by Conde Nast or the LA Times or what a loss this is. Our main focus should be on the loss of employment for many best-in-their-field staff and the obvious union busting at the root of crippling these profitable enterprises. The short term outlook is really, really bleak, and the immediate fallout on music of all kinds is going to be very real. Even if Pitchfork continues publishing reviews for as long as they can, the other arms of the company like their excellent features section have been gutted entirely. There were already many niche artists and genres whose best or only shot at building real momentum was landing a pitchfork review, and in the immediate future many of those artists will either fail to catch on with the remaining staff or get lost in the shuffle as the musical chairs competition continues and the remaining places to reliably get a review published keep falling by the wayside.

As with every time we’ve hit a collective new low as a music industry over the last few years, the “state of music journalism these days” discourse quickly spirals past being a grounded discussion of the issue at hand into something more existential. Whether its sky-is-falling doomerism or irrational “blogs are back baby” optimism, the conversation become a receptacle for our pre-existing philosophies, anxieties, and bones to pick about the larger picture, and the closing of one website or publication suddenly feels like a referendum on the very idea of music journalism. Will it continue to exist, does it “deserve” to exist, and if so, how? Is the album review dead? Does it matter? Conversations that are as inside baseball as “should album reviews be meaner or should they be nicer” and “did Pitchfork become too Poptimist” [my eyes roll into the back of my head] end up feeling like referendums on not just the field we work in but the life choices and values that lead us here. When we - as writers (aspiring or otherwise) bemoan the death of music journalism and argue over its murderer, we are really fighting a proxy war over our own insecurities, bred by the scarcity mindset. Have I devoted my life to becoming something that the world doesn’t need? Did I, as Tony Sopranos famously put it, “come in at the end” as this dinosaur was already going extinct?

So, since we’re all using this as an excuse to make this about ourselves: allow me to join in.

As someone who struggled for most of my adolescence and young adulthood to imagine what a future career for myself would look like (thanks, depression and the closet), the dream of being a music writer was one of the few paths that felt remotely like something I would enjoy doing; one of the rare things that came naturally to me as everything else in my life felt so forced. As is the case I’m sure for many a young aspiring music journalist with boomer aged parents, my father made the irresponsible decision of showing me Almost Famous at a young age, and the wide-eyed optimism of Cameron Crowe’s semi-autobiographical fantasy was enough motivation to set me off on a journey writing embarrassingly shaky self published blogs (and eventually some better ones).

As I started to approach writing more seriously, I was in desperate need of a splash of cold water to the face, and fittingly mine was delivered by LA’s own Jeff Weiss. Years before I had even started writing for bigger publications, he told me straight that the path ahead of me wasn’t much of a path at all: the old ladder of alt weeklies and local papers that his generation of writers climbed up already didn’t exist anymore in the mid 2010s, and now in 2024 that picture is even bleaker. Nonetheless, Jeff still gave me whatever advice he could and let me contribute to his site; because anyone still doing this stuff is a little crazy, and he could tell I already had the bug. I still cringe thinking about the first draft he had to red line to death in order to get to a competent enough level to publish (which taught me more about being a better writer than just about anything else), Jeff’s mix of passion and cynicism provided an important lesson: anyone who wants to do this has to do so with a certain amount of reckless abandon.

Fast forward a few years and suddenly, despite Jeff being totally right about the almost complete lack of upward mobility, a path magically appeared before me. Anyone who knows me knows the TLDR of the events: coming out as trans, starting a full time music PR job, getting noticed by Ethel Cain via something I wrote on the wonderful website Merry-Go-Round Magazine (started by peers with the express purpose of platforming new writers) and then being whisked into my own Almost Famous adventure that got me my first cover story and some bylines, including a handful of track reviews for Pitchfork. I had seemingly become the exception that proves the rule, and was starting to develop some credibility and reach that was opening doors for me. I’ll never forget the day I called my dad to tell him that I had landed the Paper cover story, and him immediately telling me that I had to re-watch Almost Famous. Maybe life could be like the fantasies I imagined from that place of adolescent hopelessness.

And yet, I found myself drifting. Even as seemingly everything was coming up Milhouse I was becoming increasingly burnt out by the grind of doing full time PR for a roster of clients I had little investment in, and even as these doors were opening for me as a music writer I was painfully aware that now even the highest echelons of music journalism were in significant peril. Even as I quit that job to pursue starting my own independent ventures, I didn’t entirely know what I was doing or how I was going to make it all work. Those drain-circling thoughts got louder and louder, and even as I started to find passion and purpose in starting my own PR company and beginning to work with friends on projects I really cared about, I couldn't shake that pit in my stomach. Quickly I realized that given the increasingly limited opportunities in the industry, it would be difficult for me to pursue pitching as a freelance writer and freelance publicist at the same time, and I made the decision to focus my efforts on the PR side of things.

At this point, I’ve made my peace with my Professional Writer career being mostly behind me, even though I plan to blog more regularly and occasionally pop back when the right opportunity presents itself. Over the last year on my own, I’ve learned that I actually do like doing PR and management – so this career pivot wasn’t entirely an act of self-preservation or giving up a dream for a more stable path. Truth be told, it isn't even that much more stable: there obviously isn’t much of a career in music PR if there are no publications left to pitch, and so even as I felt like I was saying goodbye to that dream of making a living entirely through writing about music, I knew my dreams were still tied to this possibly failing system, and as one publication shut down after another I began to panic about the whole house of cards tumbling down.

For pretty much my entire life, since being born at the tail end of the CD era in 1996, the perceived monetary value of music has been shrinking. It’s always easy to romanticize the past in hindsight, whether that be the peak of magazines in the 90s or the first blog era where it briefly felt like the promised “democratization” of the internet might buoy independent music (and as many will tell you those eras were rife with their own problems), but it's hard not to look at the last 27 years as a slow descent to this new bottom we’ve found ourselves at. And it’s probably going to get even worse before it gets better.

As Jeff describes in his recent appearance on the podcast No Tags (recorded just before the "folding in”), the kind of investigative journalism he does on vital subjects like the tragic assassination of Drakeo the Ruler and the ensuing miscarriage of justice is work he more or less finances out of his own pockets. Even someone with the advantage of building notoriety and audience before the collapse of most legacy media like Jeff is doing it for the love of the game, and as many have pointed out there’s only so much that can be done in those DIY margins. In the case of a true injustice like Drakeo, the story is well worth it, but we can’t depend on this kind of above and beyond dedication to be the norm. And as much as I think we should be creating new blogs, zines and publications as we try to imagine new ways of doing this; people with way more experience and knowledge than myself who just lost their job this week should not be expected to just “DIY or die” until that new norm is achieved. As Shawn Reynaldo said in his blog post about pitchfork, “even if there’s some sort of independent media ecosystem forming, it’s extremely fragile, and shouldn’t be seen as an adequate replacement for what’s been lost”

There’s no short term band-aid to fix any of this – short of Joe Biden announcing tomorrow that he’s going to nationalize the Conde Nast corporation as a public utility (jokes aside, some federal funding / grants for journalism, arts, and culture sure would be nice!!) – and I’m not going to offer up solutions that don't come with a lot of caveats about how much this all sucks. My hope in the future is not rooted in blind, privileged optimism that we can blog so hard that we magically start a new media economy, but rather a hope that surely there has to be a better way to do things than THIS *gestures broadly at everything*.

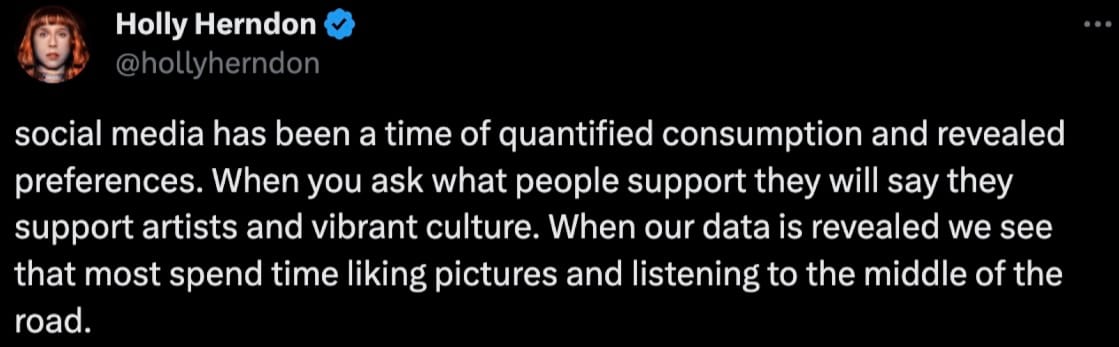

While I cannot dispute the fact that things are about to get rocky and weird, for at least a while, I am going to push back against the idea that this decline in the “value” of music and music journalism is because people don’t care. Not to single her out, because this is a version of an idea I’ve seen lobbied by all sorts of people, but there’s this tweet from Holly Herndon that I got really mad about recently and I think it’s helpful in illustrating my point here:

To give her credit, she says in the next tweet that streaming is in large part to blame for this, but the wording of this idea still rubs me the wrong way. Without putting too many words in her mouth, the “revealed preferences” part implies that data tells us what most people *actually* want more so than their expressed thoughts or feelings. Secretly, in the eyes of this pessimistic worldview, deep down most people are pigs who crave slop, even if they try to tell you otherwise. Our borderline religious obsession with data and statistics has gotten to a point where we see them as objective in a way that supersedes our own humanity, completely overlooking the power dynamic by which these devices and streaming services are specifically engineered to hijack our brain’s weaknesses and form habits. Maybe streaming services produce these data outcomes because they are deliberately trying to.

Whenever I think about these existential problems, I think back to a conversation I had in line at an Ethel Cain show just over a year ago now. I was making small talk with the guy next to me in line, and as we talked about Preacher’s Daughter I asked him how he had discovered it and he said something to the effect of “I never know where to find new music these days, but I was recommended this album and I completely fell in love with it”. Obviously Ethel Cains do not grow on trees, but I see this as a profound failure of our music industry: here is someone engaged enough to go buy tickets to shows and pay for merch when they find an artist that speaks to them, and there are dozens if not hundreds of other talented artists that in a more functional ecosystem might have been able to connect with him in the same way. Spotify’s “cold hard empirical data” will never show this!!

Things were far from perfect in the 90s, and the “monoculture” of MTV and music magazines obviously had its own litany of problems and gatekeepers but it’s inarguable to say that we weren’t collectively better at matchmaking good music to potential audiences back then. You can look at those millions of spotify users only streaming the top .01% of the world’s most popular artists and being fed milquetoast algorithm recommended playlists as “normies”, or you can view them as human beings who may be longing for something more; even if they may not even identify that desire until you provide it to them. People are ready to be activated and removed from their matrix pods if you treat them with the intelligence they deserve, and condescending to those lost in our current cultural wasteland is not the way to get them to become more conscious, active supporters of music. Inevitably there will always be people who just don’t care, people who want to only consume music passively - but we live in a society obsessed with music. Even though tik tok is a false idol golden goose that I certainly don’t think will save us, it still feels relevant that the fastest growing social media app we have is centered around music. People care more about music than ever, and as others have suggested, the fact that we are overwhelmed with choices in the digital age is an argument for even more need for music writing and human curation; a need that can be met if we simply believe in it and trust the value of the work. Some people don’t want to or simply don’t have the time to be digging for new discoveries on their own, and it’s clear the algorithms and playlists aren’t cutting it.

Paradoxically, this bleak environment that I’ve been born into is a lot of why I’m remain optimistic that we can find a path forward and start to reverse the tide and build a new future for the industry. I am that flower that grew in the desert. If you believe true art and culture died long ago, then 27 year olds writing hand wringing essays about the state of journalism shouldn't exist, let alone the people even younger and more passionate about this stuff than I. The perceived economic value of music has been systematically devalued by streaming companies in an attempt to make perhaps the most famously exploitative culture industry even more exploitative, and yet somehow there are so many people my age that are hungry for and demanding better. Because the real value of music and its ability to connect us hasn’t changed at all.

Music Journalism is not dead, and it isn’t in trouble because people stopped caring about music or because pitchfork went pop or any of the other crackpot theories being tossed around. Music journalism has been crippled by corporate incompetence and unwillingness to shift power towards the workers; it has been killed by short sighted decisions, by an inability for the higher ups to accept personal accountability. Music journalism’s attempted assassination is happening because those in power have chosen the path of least personal resistance, jettisoning invaluable writers and editors for the fact that they themselves refuse to accept accountability or acquiesce to current realities as employees already have.

Pitchfork was not a loss leader, it was not a failing enterprise being kept alive past its sell by date out of corporate generosity. As those inside and outside the Condé Nast building will tell you, it was humming along as one of the highest trafficked websites in their portfolio. Beyond the gendered insult added to injury of folding it underneath the umbrella of Gentleman Quarterly, the attempt to frame this as a “re-structuring” is nothing more than a failed attempt at PR spin on Union busting. Facing the choice to either downsize the Conde Nast offices that undoubtedly costs a fortune in rent / other overhead or fire all the writers and make their own asset less valuable – they are choosing to let it burn. Over and over again the venture capitalists and Anna Wintours of the world are given the worlds easiest trolley car problem and they fail every time; because being in power is never having to admit you were wrong.

You can say that my dreams of having an actually functional, worker owned and operated media ecosystem are a mix of socialist wishcasting and inherited nostalgia for an era I didn’t live through, but I’m not naive to think things were easy in the past or will ever be easy. The music journalism industry has always been a boondoggle that exploits the willingness of people to do things for free or very cheap, where you are constantly told you’re working a “dream job” so that you never ask for more money or better conditions. That doesn’t mean it can’t be better.

One of the retorts you often get from pessimists trying to shoot down the possibility of progress in this industry is that any revitalization of arts and culture would require people changing their consumption habits on a mass scale, something that rarely if ever happens. People can say they want more music journalism all they want, but how are we going to get people to start paying for something they’ve been conditioned to expect for free?

This problem, like all the other problems we face, feels impossible to solve without a change in perspective.

I think an awful lot about a conversation I had in college with a friend of mine Paul, in which the two of us were bemoaning the general State of Things, and I expressed feeling hopeless that I am essentially powerless to change the world on my own. What he told me will stick with me forever - “maybe it’s not our job to change the world”. At first, I saw this thought as nihilistic, but it’s actually the opposite. We don’t have to change the world, we just have to change ourselves. A massive change across society becomes easier to conceptualize when we think of it as wide swath of people all individually making a choice. A choice to be more active participants in our community, a choice to keep going.

We need a renaissance of music blogging and curation by humans for humans, but we need that to happen alongside new cultural institutions that can provide real jobs and budgets for real journalism. We need new platforms for sharing not based around algorithmic churn, we need real physical spaces to come together and not just digital ones. We need arts and culture to continue to thrive, and we need to ignore the people cynically trying to depreciate its value.

How we get there is obviously tricky, but nothing is going to be built unless we believe that it can be.